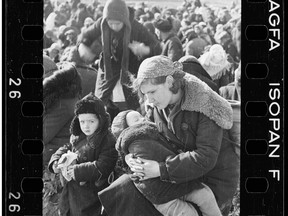

The single most comprehensive exhibition on the camp opens Jan. 10 in Toronto, just ahead of the 80th anniversary of its liberation

Published Jan 10, 2025 • Last updated 7 minutes ago • 6 minute read

Among the vivid memories Nate Leipciger has of Auschwitz is his arrival at the Nazi death camp on Aug. 2, 1943, with his father, Jack, from the Jewish ghetto in Sosnowiec, 35 kilometres to the north.

“I had no idea where we were. It was unreal and beyond my imagination,” recalled Leipciger, 96, a well-known figure in Holocaust education in Toronto, in a Post interview. “After being tattooed (with the number 133628) and inducted as a prisoner and losing my identity, I thought this was hell on earth, from which I had little or no hope of getting out. I was in total despair. Only my father’s presence gave me some hope.”

Advertisement 2

THIS CONTENT IS RESERVED FOR SUBSCRIBERS

Enjoy the latest local, national and international news.

- Exclusive articles by Conrad Black, Barbara Kay and others. Plus, special edition NP Platformed and First Reading newsletters and virtual events.

- Unlimited online access to National Post and 15 news sites with one account.

- National Post ePaper, an electronic replica of the print edition to view on any device, share and comment on.

- Daily puzzles including the New York Times Crossword.

- Support local journalism.

SUBSCRIBE FOR MORE ARTICLES

Enjoy the latest local, national and international news.

- Exclusive articles by Conrad Black, Barbara Kay and others. Plus, special edition NP Platformed and First Reading newsletters and virtual events.

- Unlimited online access to National Post and 15 news sites with one account.

- National Post ePaper, an electronic replica of the print edition to view on any device, share and comment on.

- Daily puzzles including the New York Times Crossword.

- Support local journalism.

REGISTER / SIGN IN TO UNLOCK MORE ARTICLES

Create an account or sign in to continue with your reading experience.

- Access articles from across Canada with one account.

- Share your thoughts and join the conversation in the comments.

- Enjoy additional articles per month.

- Get email updates from your favourite authors.

THIS ARTICLE IS FREE TO READ REGISTER TO UNLOCK.

Create an account or sign in to continue with your reading experience.

- Access articles from across Canada with one account

- Share your thoughts and join the conversation in the comments

- Enjoy additional articles per month

- Get email updates from your favourite authors

Article content

About 10 members of his family, including his mother and sister, were murdered in the gas chambers of Birkenau, the largest of the nearly 50 sub-camps collectively known as Auschwitz.

The largest, deadliest and most notorious of the Second World War Nazi death camps — and that’s saying something — Auschwitz still conjures images of gas chambers, skeletal inmates in striped uniforms, barbed wire, crammed boxcars, crematoria, and chimneys belching smoke and human ash. It is synonymous with killing on a modern, industrial scale.

It became that through the sheer number of its victims: 1.3 million people were deported to Auschwitz between June 1940 and the summer of 1944. Of those, 1.1 million were Jews, 900,000 of whom were gassed shortly after arrival. The death toll included up to 75,000 non-Jewish Poles, 21,000 Roma, 14,000 Soviet prisoners of war, and as many as 15,000 in other categories — criminals, homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses and “undesirables.” Many inmates were worked to death in surrounding factories. In January 1945, the camp’s Soviet liberators encountered 7,600 survivors in Auschwitz’s three main camps.

Advertisement 3

Article content

Opening at the Royal Ontario Museum today, just ahead of the 80th anniversary of the liberation of the camp on Jan. 27, 2025 (also the annual International Holocaust Remembrance Day), the hauntingly named “Auschwitz. Not long ago. Not far away,” bills itself as the single most comprehensive exhibition dedicated to the history of the concentration and extermination camp.

A preview by the Post revealed an exhibition that is at once stunning and numbing, comprising more than 500 original artifacts, and hundreds of photographs, charts, drawings, correspondence and diagrams on loan mainly from the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum and more than 20 other institutions and private collections around the world. Many of the objects are being shown in Canada for the first time.

Recommended from Editorial

-

Holocaust survivor not surprised Canada won't reveal names of alleged Nazis

-

Violins that belonged to Holocaust victims used in Toronto performance

Across 1,300 square metres in the ROM’s Michael Lee-Chin Crystal, the artifacts, augmented by survivors’ recorded testimonies, “are the traces of genocide, the remnants of a murdered people, and the material evidence of crimes against humanity,” writes curator Paul Salmon in the exhibit’s 242-page catalogue. “They are what remain despite the perpetrators’ attempts to conceal their crimes.”

By signing up you consent to receive the above newsletter from Postmedia Network Inc.

Article content

Advertisement 4

Article content

Displays explore the birth and rise of Nazism after the First World War, and offer a history of the 1,000-year-old town of Oswiecim, a dot on the map in Upper Silesia where the Nazis constructed their sprawling complex in occupied Poland.

Grim reminders of the gas chambers are seen in the tins that contained the Zyklon B pellets and in a reproduction of the wire mesh column used to lower the pellets into the chamber.

A large glass case is jam-packed with the quotidian belongings of newly-arrived prisoners: shaving material, perfume bottles, eyeglasses, hair brushes, bowls and buttons. There was so much of this property that it was stored in 30 barracks collectively called “Kanada,” named for the country imagined to be brimming with riches.

There’s Canadian content: a wood sculpture by Felix Kohn, and two charms crafted from a bullet casing by Esther Friedlander, who smuggled out the items from the munitions factory where she toiled. Both former inmates would live in Canada.

A child’s tiny, battered brown shoe, draped with a lone sock, poke at the heart like a sharp stick. As many as 1.5 million Jewish children were murdered or died at the hands of Nazis or their collaborators.

Advertisement 5

Article content

The exhibit owes its origins to the family-owned Spanish company Musealia, which mounts touring exhibitions. The spark was the sudden death of the 26-year-old brother of the company’s director, Luis Ferreiro, in 2008. Ferreiro found comfort in a gift, the bestselling book Man’s Search for Meaning by the psychotherapist and philosopher Viktor Frankl, a survivor of Auschwitz whose pregnant wife, parents and brother all perished.

Buoyed by the book’s lessons of survival and finding purpose, even in the worst possible places, Ferreiro, a non-Jew, set about what he called “a moral necessity to do something. It was always about Auschwitz for me.”

Working with the Auschwitz Museum and other lenders was a drawn-out but rewarding process. “We knocked on many doors,” Ferreiro told the Post in a phone interview. “I never got no for an answer.”

The exhibit finally opened in Madrid in 2017 and has toured in New York, Kansas City, the Ronald Reagan Library in Simi Valley California, Malmo, Sweden, and Boston. Ferreiro estimates that between 1.5 and 2 million people have viewed it.

Advertisement 6

Article content

Ferreiro’s outreach led him to the exhibit’s chief curator, Robert Jan van Pelt, a professor at the University of Waterloo’s School of Architecture and among the world’s leading experts on Auschwitz.

A set of objects that are especially poignant for van Pelt are among the smallest and most modest in the exhibit: About 200 buttons, some metal, some covered in fabric, many frayed, that were yanked from inmates’ clothing.

Van Pelt relates a story told to him by Rainer Höss, grandson of Auschwitz commandant Rudof Höss, one van Pelt said he will repeat when he leads tours at the ROM.

Helping oneself to the clothes of those freshly murdered was routine among the camp’s leaders and their families. When Hedwig Höss, Rudolf’s wife and Rainer’s mother, heard that Jews had come to the camp from the Netherlands or Hungary, she believed they were wealthier than most other arrivals and their clothes were of better quality. So she sent someone to the Rampe (arrival ramp) to fetch the nicer pieces, shed once their owners were forced to strip prior to being gassed. The clothes were cleaned, but the buttons were removed and replaced with others.

Advertisement 7

Article content

“Why didn’t Mrs. Höss want her children, who were given the clothing of Jewish children, to touch the buttons that Jewish fingers had touched?” van Pelt asked in a Post interview. Precisely because, he replied, they were the last things Jewish fingers had touched.

“I don’t want to say they left existential fingerprints,” van Pelt said, “but in a sense, they do, and Mrs. Höss realized that.” She could deal with the garment but not the buttons.

The exhibit comes amid skyrocketing antisemitism the world over, and when it appears knowledge about the Holocaust is fading. A Leger Marketing poll in 2020 found that only 43 per cent of Canadian respondents knew that six million Jews perished in the Holocaust. Among those aged 18 to 24, it was 40 per cent.

“It’s not easy to go to a museum to learn about the particular story of Auschwitz, but sometimes the things that are more difficult are the ones that are more necessary,” noted Ferreiro.

The ROM’s mission, museum director and CEO Josh Basseches told the Post, is “to help people understand the past, make sense of the present, and come together to shape a shared future.”

Advertisement 8

Article content

With the Auschwitz exhibit, “we could not imagine an exhibition that more materially fulfilled our mission.”

The museum says there is a deliberate attempt to avoid “gratuitous depictions of violence.”

The ROM is the only Canadian stop on the exhibit’s international tour. The museum offers extensive educational programs and there is no admission charge for Grade 6-12 students in visits organized by Ontario-based schools.

The exhibit runs to Sept. 1, 2025.

– Ron Csillag is a freelance writer in Toronto whose mother, Irene Csillag, survived Auschwitz.

Our website is the place for the latest breaking news, exclusive scoops, longreads and provocative commentary. Please bookmark nationalpost.com and sign up for our newsletters here.

Article content

.png)

4 hours ago

7

4 hours ago

7

Bengali (BD) ·

Bengali (BD) ·  English (US) ·

English (US) ·