New year, new milestone: A cosmic quirk of nature has allowed the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to capture images of 44 individual stars in a galaxy halfway across the observable universe — this region is so distant that astronomers once deemed identifying individual stars in it impossible, like using binoculars to spot dust grains inside craters on the moon.

"I never dreamed of Webb seeing them in such large numbers," Rogier Windhorst, an astronomer at the Arizona State University, who was part of the discovery team, said in a statement. "And now here we are observing these stars popping in and out of the images taken only a year apart, like fireflies in the night. Webb continues to amaze us all."

Beyond being a technological feat, the discovery provides an opportunity to probe the elusive behavior of dark matter, researchers say.

The newly discovered 44 stars — the largest collective of stars ever observed in the distant universe — belong to a distant, hidden galaxy whose light has been warped into the strikingly long tendril in the center-left of the image, nicknamed the Dragon. Light from the Dragon's home galaxy began journeying through space roughly 6.5 billion years ago, when the universe was half its present age. By analyzing colors of each of the newfound stars within the Dragon, the researchers inferred they are red supergiants in the final stages of their lives, like the familiar — perhaps soon-to-explode — Betelgeuse perched on the right shoulder of the constellation Orion.

The Dragon is, in fact, a mishmash of several duplicated images of a single background spiral galaxy, stunning cosmic mirages caused by its chance alignment behind the Abell 370 galaxy cluster. Abell 370 itself is a crowded home to an astounding assortment of several hundred galaxies bound together by gravity about 4 billion light-years away from us in the constellation Cetus. About a hundred other far-flung, unseen galaxies appear as faint wisps of light entangled within the galaxy cluster, which acts as a massive, intervening cosmic lens, magnifying and distorting light from these background galaxies and making them detectable with powerful telescopes like the JWST. Scrutinizing these arcs of light allows astronomers to study remote galaxies in much more detail than would otherwise be possible.

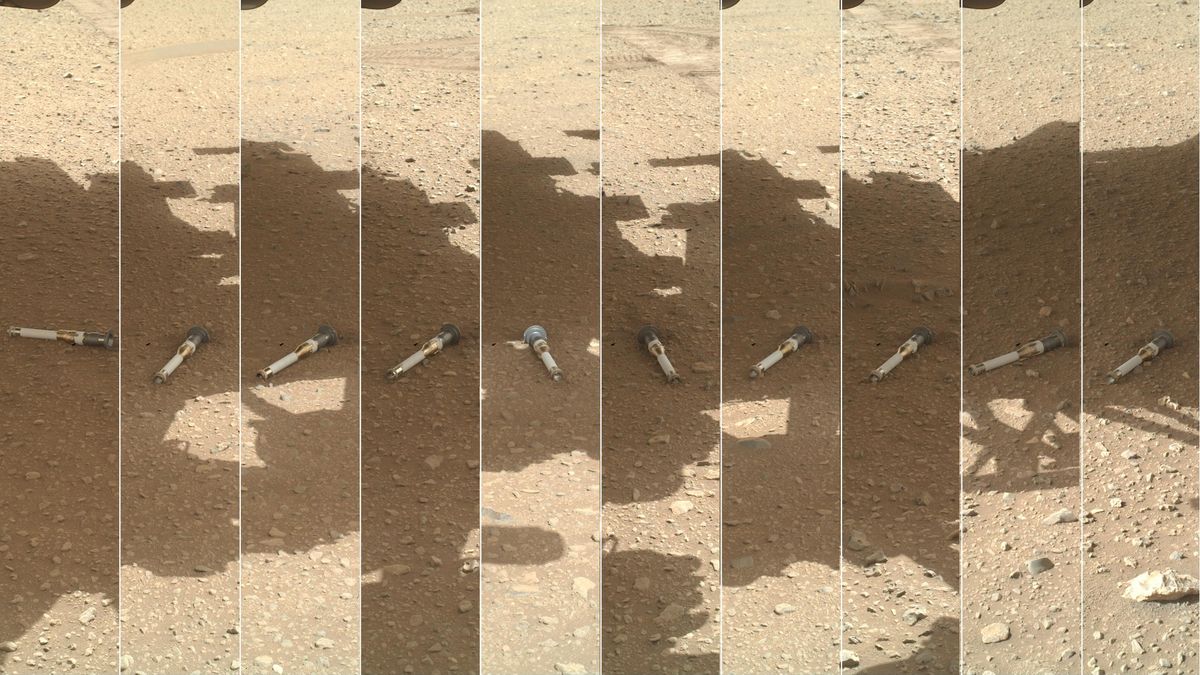

Fengwu Sun, a postdoctoral scholar at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian and a co-author of the study, stumbled on the trove of stars while looking for a background gravitationally lensed galaxy in images of the Dragon taken by the JWST in 2022 and 2023. "When we processed the data, we realized that there were what appeared to be a lot of individual star points," he said in the statement. "It was an exciting find because it was the first time we were able to see so many individual stars so far away."

But even the mighty JWST would struggle to identify such a high number of bright stars without the serendipitous assistance of floating stars within Abell 370, which happened to briefly line up with stars in the background hidden galaxy and further gravitationally magnify them, according to a paper Sun and his colleagues published Monday (Jan. 6) in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Due to subtle variations these events caused in the gravitational lensing landscape, the stars' brightnesses changed over time, causing them to "appear and disappear from image to image like a twinkling Christmas tree," study co-author Nicholas Foo of the Arizona State University said in the statement.

A study about these results was published on Jan. 6 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

.png)

1 day ago

11

1 day ago

11

Bengali (BD) ·

Bengali (BD) ·  English (US) ·

English (US) ·