My baptism into the hidden epidemic of wrongful convictions came more than two decades ago when a Bronx detective confided that he knew two men languishing in prison for the 1990 murder of a Manhattan nightclub bouncer were innocent. How could he be so sure? “Because I know who did it,” he said.

It was a conversation that changed my life — and gave me new purpose as a journalist.

As a producer for NBC’s “Dateline” for nearly 30 years, I’ve been immersed in every aspect of the justice system. I’ve spent years embedding with detectives, prosecutors and defense attorneys. I’ve heard indelible stories from countless victims of crime. I’ve interviewed a host of judges, jurors and people condemned to death. And I’ve spent hundreds of days inside prisons.

My decades of reporting helped free six innocent men.

Dan Slepian speaks at the launch of the Reform Alliance at John Jay College in New York on Jan. 23, 2019.Nicholas Hunt / Getty Images for The Reform Alliance file

Dan Slepian speaks at the launch of the Reform Alliance at John Jay College in New York on Jan. 23, 2019.Nicholas Hunt / Getty Images for The Reform Alliance fileMy prolonged proximity to all the facets of our justice system has spotlighted one inescapable issue — the disturbing frequency with which innocent people are sent to prison and the staggering difficulty of rectifying that injustice, even when it is obvious.

Statistics underscore this grim reality. No one knows how many innocent people are in prison, but Barry Scheck, a co-founder of the Innocence Project, believes that the most realistic studies indicate at least 100,000 of the nearly 2 million people locked up across America could be wrongfully convicted. But, in a span of 30 years, only 3,500 people have been exonerated.

We know the biggest contributors to wrongful convictions: Unreliable eyewitnesses. False confessions, often extracted under duress. Ineffective defense attorneys. Witnesses with incentives to lie. Police and prosecutorial misconduct. Junk forensic science.

These problems feature prominently in the plight of the six freed men whose cases I investigated over two decades, as featured in my recent book, “The Sing Sing Files,” and in the NBC News Studios docuseries “The Sing Sing Chronicles.”

— Jon-Adrian “JJ” Velazquez, sentenced to 25 years to life for the 1998 murder of a retired policeman in Harlem. The case against him was built on eyewitness identification; not a shred of physical or forensic evidence linked him to the scene. He even had two alibi witnesses. My 20-year investigation revealed a pattern of questionable police and prosecutorial tactics, as well as two eyewitnesses who recanted and critical evidence his attorneys never saw before his trial. He served nearly 24 years.

— David Lemus and Olmedo Hidalgo, each sentenced to 25 years to life for the 1990 murder of a Manhattan nightclub bouncer. The two men had never met. The case against them relied mainly on eyewitness identification. My investigation uncovered new evidence and misconduct, and sparked a court hearing. I also interviewed the actual gunman, which caused key eyewitnesses to acknowledge they were wrong. Each man served 15 years.

— Eric Glisson, sentenced to 25 years to life for the 1995 murder of a cabdriver in the Bronx. My investigation revealed fabricated evidence and coercive police tactics, contributing to a broader debate about police reform and the integrity of criminal investigations. He was imprisoned for nearly 18 years.

— Johnny Hincapie, sentenced to 25 years to life for the 1990 robbery and murder of a tourist from Utah on a subway platform in Manhattan. His conviction was based on a false, coerced confession he gave when he was 17 years old. He spent 25 years behind bars.

— Richard Rosario, sentenced to 25 years to life for the 1996 murder of a teenager in the Bronx. He was arrested and convicted based solely on eyewitness testimony — despite having provided detectives with the names of 13 alibi witnesses who would swear he was a thousand miles away in Florida at the time of the crime. Authorities — and his trial attorneys — didn’t follow up with those witnesses, who included a police officer, a federal corrections officer and a pastor. I interviewed most of them, ultimately leading to his release. He served 20 years.

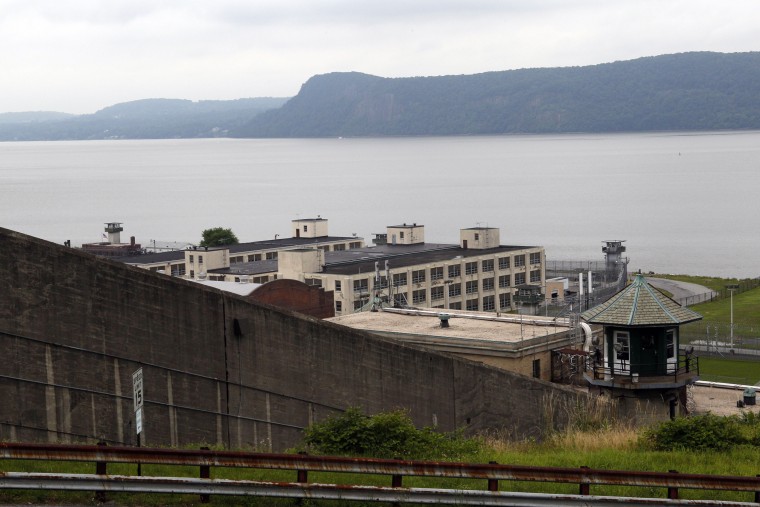

Sing Sing Correctional Facility overlooking the Hudson River.Mary Altaffer / AP file

Sing Sing Correctional Facility overlooking the Hudson River.Mary Altaffer / AP fileThrough my work, I’ve come to understand the deeper pathology of mass incarceration. We have created a false narrative that stokes demands for politicians to be “tough on crime,” but the result too often has undermined public safety rather than enhanced it.

Consider the astonishingly high recidivism rates for people who have done time. Roughly 70% of people released from prison are rearrested within three years, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. Yet even though studies have found that prison education programs reduce recidivism by almost 45%, funding for such programs remains woefully inadequate — and some facilities offer no educational opportunities at all.

And while the use of solitary confinement often is justified as a necessary tool for discipline and safety, studies have shown that prolonged isolation increases rates of violence and mental illness, which significantly affect rehabilitation and reintegration into society. Still, tens of thousands of people in the United States are subjected to solitary confinement every day, according to the Vera Institute of Justice, a nonprofit organization that focuses on criminal justice reform.

There is little public outcry to improve prison conditions when people remain convinced that crime is epidemic: Year after year, they tell pollsters it’s more violent than it has ever been. But the reality is that for more than 15 years, the United States has seen a remarkable trend — all but five states have reduced most crime rates.

Even for those accused of petty offenses, the system often wreaks havoc. People can lose their jobs, their homes and their children. And even winning release from prison in those rare cases doesn’t spell total freedom.

In August 2021, New York’s governor granted JJ Velazquez clemency, reducing his sentence and allowing him to go home after he had spent almost a quarter-century in a cell. But his conviction wasn’t vacated, and he was subject to strict parole requirements, like adhering to a 9 p.m. curfew, regularly reporting to a parole officer and obtaining a letter if he ever wanted to travel out of state.

It was only this September that he finally won his exoneration — based on DNA testing that could have cleared him years ago.

“This isn’t a celebration,” he said outside the courtroom. “This is an indictment of the system.”

.png)

1 week ago

11

1 week ago

11

Bengali (BD) ·

Bengali (BD) ·  English (US) ·

English (US) ·